El Niño is a naturally occurring climate phenomenon with the power to increase global temperature. It arrives every two to seven years and stays for about 12 months. Scientists speculate that it has done this for millennia.

But today’s El Niño events occur in the

context of climate change. The summer of 2023 was

the earth’s hottest since global record-keeping began in 1880. In Canada alone, people experienced

the worst wild-fire season on record.

By October 2023, a major tributary to the once-mighty Amazon River fell to

its lowest level in more than a century. Families living on rivers across the Amazon Basin, including thousands of Indigenous communities, faced serious risk. Without healthy rivers they lost food sources, livelihoods, and access to health care.

In this article, we’ll explain how El Niño unfolds. We’ll explore its impact in regions already at the mercy of global warming. We’ll describe the ‘super El Niño’ some are predicting for 2024. And we’ll share how you can help.

El Niño on the move

The El Niño phenomenon is part of a larger oscillation, along with its opposing climate pattern,

La Niña. El Niño is known for its unusually warm sea temperatures in the equatorial Pacific.

La Niña is known for its cooler readings.

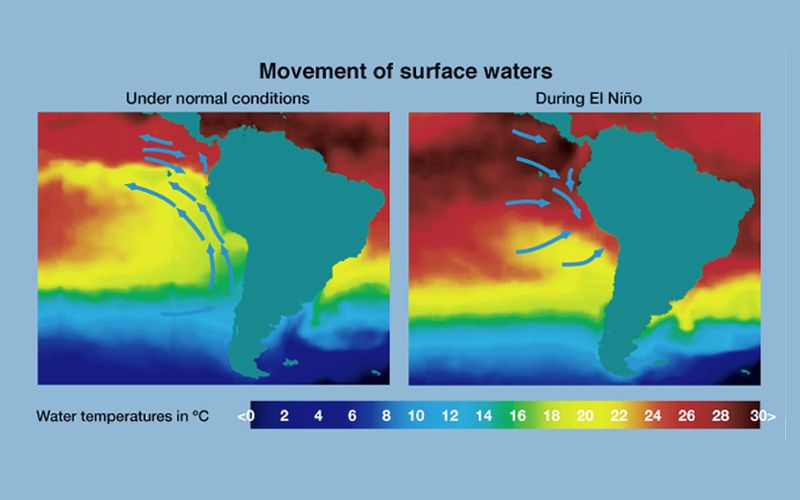

El Niño has the power to affect the entire planet. It moves trade winds and ocean surface waters eastward toward South America. It continues onward to Australia and Indonesia. It connects to North America and Africa through the jet stream, high up in the atmosphere.

Map: Wikimedia Commons

Map: Wikimedia Commons

The modern-day, ‘super El Niño’

El Niño got its name in the 1600s, from fisherman off the coast of Peru. The winds near Christmastime were unusually warm. They christened the weather pattern “the little boy” in Spanish … “the Christ Child” when capitalized.

But the modern El Niño is neither meek nor mild. When

scientists announced in 2023 that the phenomenon was emerging again, they warned it could be a bad one. Some used the term ‘super El Niño.’

Rising temperatures in the equatorial Pacific region create stronger El Niño events, they explained. This could prompt severe climate crises in 2024.

Not only would a ‘super El Niño’

be fueled by a hotter planet, but it could also

raise global temperatures even higher. El Niño releases heat into the atmosphere. The stronger the event, the more heat released. And the more severe the climate disasters.

This family’s home can no longer float on this dried-up tributary to the Amazon River. El Niño is a major contributing factor to the devastating drought. Photo: Edmar Barros/AP

This family’s home can no longer float on this dried-up tributary to the Amazon River. El Niño is a major contributing factor to the devastating drought. Photo: Edmar Barros/AP

El Niño’s climate crises

As El Niño emerged in the summer of 2023, people around the globe began feeling its devastating power.

By August 2023,

rivers were overflowing in Ecuador and Peru, placing many in danger. This happened due to an increase in precipitation, caused by convection over warm ocean waters.

By September 2023, drought and wildfires threatened communities in Australia,

Indonesia and beyond. The temperature in some Australian towns was 29 degrees above normal. Authorities called fire conditions ‘catastrophic’.

By October 2023, 150 river dolphins were found dead in the Amazon Basin. At nearly 40 degrees Celsius, the water was too warm for them to survive. People across the region were enduring a

record-breaking drought, with El Niño a main factor.

By November 2023, people in parts of

Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia were overwhelmed by torrential rainfall and deadly flooding. Just months earlier, they’d been fleeing severe drought, in search of food and help.

Somalis fleeing rising floodwaters climb into rescue boats. Torrential rainfall, exacerbated by El Niño, led to a state of emergency in October of 2023. Photo: Muhadin Abdullahi

Health issues on the rise

Somalis fleeing rising floodwaters climb into rescue boats. Torrential rainfall, exacerbated by El Niño, led to a state of emergency in October of 2023. Photo: Muhadin Abdullahi

Health issues on the rise

Anywhere it strikes, El Niño fuels a

wide range of health problems—including heat stress, fire-related respiratory illnesses, disease outbreaks and malnutrition when crops die. Flood-related health risks range from drowning and hypothermia to infectious illnesses like dengue or cholera.

El Niño and hunger

El Niño can destroy food sources, withering crops and vegetable gardens or washing them away. In the tropical Pacific, fish populations drop due to ocean changes. This in turn damages livelihoods, leaving families without income to buy food for

malnourished children.

According to the World Food Programme, here are regions most likely to suffer hunger and malnutrition due to El Niño-related crop challenges:

- Southern Africa and West Africa (cereals such as corn, also, cocoa).

- Central America (corn and beans).

- The Caribbean (vegetables such as tomatoes, cauliflower, sweet peppers and leafy greens, as well as grain to feed chickens and other livestock).

- Asia and Southeast Asia (cotton, pulses, oilseeds, palm, rice and sugar).

- Specific countries including Ethiopia (grazing lands, feed for livestock), Indonesia (coffee), the Philippines and Sudan.

In 2016, El Niño pulled 60 million people around the world into hunger and malnutrition. As crops died, so did livestock critical for families’ nutrition and livelihoods. Photo: Kalebbo Geoffrey Denye

Fishing threatened by El Niño

In 2016, El Niño pulled 60 million people around the world into hunger and malnutrition. As crops died, so did livestock critical for families’ nutrition and livelihoods. Photo: Kalebbo Geoffrey Denye

Fishing threatened by El Niño

El Niño changes ocean waters in the Pacific, reducing the volume of tiny phytoplankton which

make other marine life possible. Higher water levels can

flood on-shore shrimp producing areas.

Fishing is the primary industry in Chile, Ecuador and Peru, where people rely on anchovy, hake, mackerel, sardine, shrimp and tuna to feed their children and earn a living. With supplies down, shortages are forecast—both locally and globally.

Fishing families in Chile, Ecuador and Peru rely on ‘normal’ years to keep their livelihoods afloat. During El Niño, fish populations routinely plunge in the equatorial Pacific. Photo: Chris Huber

Fishing families in Chile, Ecuador and Peru rely on ‘normal’ years to keep their livelihoods afloat. During El Niño, fish populations routinely plunge in the equatorial Pacific. Photo: Chris Huber

El Niño’s impact for the world

El Niño’s cruelest effects are felt by the world’s poorest families—especially those in rural or remote areas, where survival is tied directly to climate. But its impact in places like Brazil, Somalia, India and Indonesia is felt all around the globe.

Here are some examples:

In Somalia, people fetch water from holes dug in the dry bed of River Dawaa. Shifting weather patterns and more frequent droughts are moving water further beyond their reach. Photo: Gwayi Patrick

In Somalia, people fetch water from holes dug in the dry bed of River Dawaa. Shifting weather patterns and more frequent droughts are moving water further beyond their reach. Photo: Gwayi Patrick

El Niño and the world’s most vulnerable families

World Vision teams are working with communities suffering the combined effects of El Niño and global warming. We are:

- Providing emergency water and building water and sanitation systems.

- Distributing emergency food to families facing droughts, floods and fires

- Strengthening health systems so people receive the help they need the malnutrition, diseases and respiratory illnesses

- Protecting children in the danger and chaos of natural disasters, or as families migrate in search of food.

- Keeping education alive in our child-friendly spaces, and camps for people displaced by natural disasters

- Preparing and equipping communities to respond to disasters in the future.

- Advocating with Canada’s government for funding to assist people bearing the brunt of climate change.

Food supplies drop in Ecuador each time El Niño hits. In this country and others affected by the phenomenon, World Vision is there with emergency food. Photo: Chris Huber

Food supplies drop in Ecuador each time El Niño hits. In this country and others affected by the phenomenon, World Vision is there with emergency food. Photo: Chris Huber

Our work in the Amazon Basin

As El Niño worsens extreme drought in the Amazon, river levels have reached historic lows. This has left thousands of families isolated. More than 200,000 children are at risk.

Families in the Amazon count on the rivers for fish, water and livelihoods, and as well as to travel by boat for emergency supplies, health services and education. Now, the warm waters are killing fish populations. Water travel is a challenge and, in some cases, impossible.

As of November 2023, World Vision emergency teams were:

- Coordinating with local governments and civil protection authorities to identify humanitarian needs, especially to ensure children’s access to food, water, education and health services.

- Mobilizing resources and engaging with donors to provide water and food to families affected by the drought.

- Prepositioning supplies in the area so we can scale up the response according to the needs in each affected territory.

- Networking in the area through churches, other agencies and communities to identify the location of the most vulnerable children and their families and reach out to them.

In May 2023, children on the Amazon’s rivers were still running to greet the World Vision Hospital Boat for check-ups and medical care. Water levels have dropped many metres since then, making some rivers impassable. Photo: Klezer Gaspar

To help families affected by El Niño and climate change, visit our Emergency Response page.